Since 2017, Dora Matzke and I have been teaching the master course “Bayesian Inference for Psychological Science”. Over the years, the syllabus for this course matured into a book (and an accompanying book of answers) titled “Bayesian inference from the ground up: The theory of common sense”. The current plan is to finish the book in the next few months, and share the pdf publicly online. For now, you can click here or on the cover page below to read the first 53 pages. Today we are adding the first two content chapters: “Probability belongs wholly to the mind?” and “Epistemic and aleatory uncertainty”.

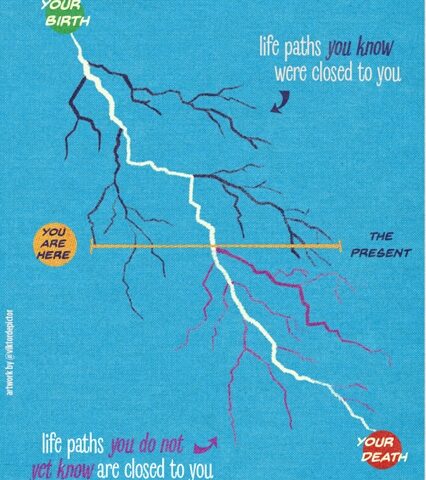

Is the universe deterministic? The question has zero practical relevance, but at the same time one cannot help but wonder whether there is any other question worth studying 🙂 Determinism is also an interesting theme running through the Matrix movies. Consider for instance the following dialogue:

Merovingian: “It is, of course, the way of all things. You see, there is only one constant, one universal, it is the only real truth: causality. Action–reaction; cause–and effect.”

Morpheus: “Everything begins with choice.”

Merovingian: “No. Wrong. Choice is an illusion, created between those with power, and those without.(…) This is the nature of the universe. We struggle against it, we fight to deny it, but it is of course pretense, it is a lie. Beneath our poised appearance, the truth is we are completely out of control. Causality. There is no escape from it, we are forever slaves to it. Our only hope, our only peace is to understand it, to understand the ‘why’.” [The Merovingian stands up from the table]

Persephone: “Where are you going?”

Merovingian: “Please, ma cherie, I’ve told you, we are all victims of causality. I drink too much wine, I must take a piss. Cause and effect. Au revoir.”

It seems that the Merovingian was an avid student of Schopenhauer, who, in 1841, made a similar claim, with comparible gusto:

“You can do what you will: but at each given moment of your life you can will only one determined thing and by no means anything other than this one. (…)

So, throughout this ever increasing heterogeneity, incommensurability and unintelligibility of the relation between cause and effect, has the necessity it presupposes also decreased at all? In no way, not in the slightest. As necessarily as the rolling ball sets the one at rest in motion, so too must the Leyden flask discharge itself when touched by the other hand, so must arsenic kill any living thing, so must the seed grain that was stored dry and showed no alteration through millennia germinate, grow and develop into a plant as soon as it is placed in the appropriate soil and exposed to the influences of air, light, heat and moisture. The cause is more complicated, the effect more heterogeneous, but the necessity with which it occurs is not one hair’s breadth smaller. (…)

It is definitely neither metaphor nor hyperbole, but a quite dry and literal truth, that just as a ball cannot start into motion on a billiard table until it receives an impact, no more can a human being stand up from his chair until a motive draws or drives him away: but then his standing up is as necessary and inevitable as the ball’s rolling after the impact. (…)

Under presupposition of free will each human action would be an inexplicable miracle — an effect without cause. (…)

Everything that happens, from the greatest to the smallest, happens necessarily. Whatever happens, necessarily happens. Whoever is alarmed at these propositions still has some things to learn and others to unlearn: but after that he will recognize that they are the most abundant source of comfort and relief. — Our deeds are truly no first beginning, and so in them nothing really new attains existence: rather through what we do, we merely come to experience what we are. (…)

Wishing that some incident had not happened is a foolish self-torment: for it means wishing something absolutely impossible, and is as irrational as the wish that the sun should rise in the West. Because every happening, great or small, occurs strictly necessarily, it is totally vain to reflect on how trivial and accidental were the causes that brought about that incident and how very easily they could have been different. For this is illusory, in that they all occurred with just as strict a necessity and had their effect with just as much power as those in consequence of which the sun rises in the East. Rather we ought to regard events as they occur with the same eye as the print that we read, knowing full well that it stood there before we read it.”

References

Wagenmakers, E.-J., & Matzke, D. (in preparation). Bayesian inference from the ground up: The theory of common sense.

Wagenmakers, E.-J., & Matzke, D. (in preparation). Bayesian inference from the ground up: Common sense in practice.