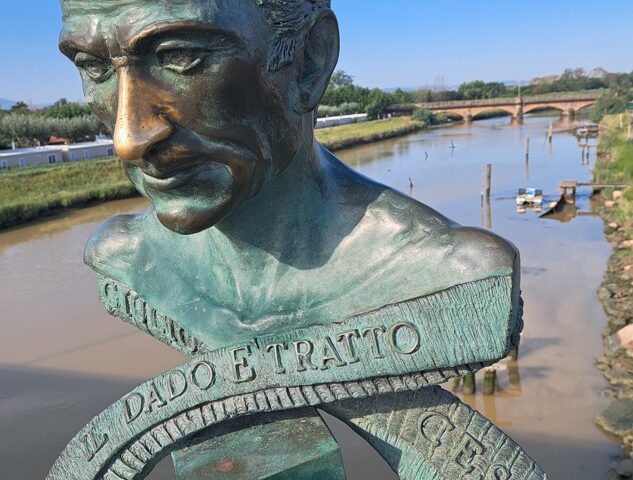

Mounted on a bridge across the river Rubicon, the bust of Julius Caesar eyes the Adriatic sea. Caesar’s nose is shiny, perhaps (but his is speculative, based on limited observations) because passersby feel tempted to touch it with their index finger. A high resolution version is available here (CC-BY). Photo taken by Eric-Jan Wagenmakers, August 4, 2024.

In 49 BC, Julius Caesar led his legion across the border river Rubicon in the direction of Rome, thereby prompting a civil war. Caesar is said to have marked this irreversible and monumental decision with the words “alea iacta est” (the die is cast; in modern Italian, “Il dado è tratto”).

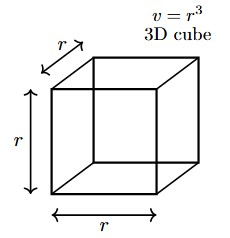

Caesar probably did not utter the words “alea iacta est” when he crossed the Rubicon. Instead, Classicists believe that Caesar quoted the famous Greek playwright Menander (c. 342/41 – c. 290 BC) and said “anerriphtho kybos” (note the Greek ancestry of the word “cube”). The Menander version is best translated as “Let the die be cast!” which has a slightly different meaning (i.e., “game on!” or “let the game be ventured”).

In our free course book “Bayesian inference from the ground up: The theory of common sense“, we stress the difference between two kinds of uncertainty that are usually both present in a Bayesian analysis: epistemic uncertainty (which is due to a lack of knowledge) and aleatory uncertainty (which is due to sampling variability). Even when we know a die to be fair (i.e., there is zero epistemic uncertainty), the concrete outcome is still (in practice) up in the air — this is due to aleatory uncertainty. One way in which students might remember that “aleatory uncertainty” means “sampling variability” is to recall the words that Ceasar probably did not speak upon crossing the Rubicon.

About The Author

Eric-Jan Wagenmakers

Eric-Jan (EJ) Wagenmakers is professor at the Psychological Methods Group at the University of Amsterdam.