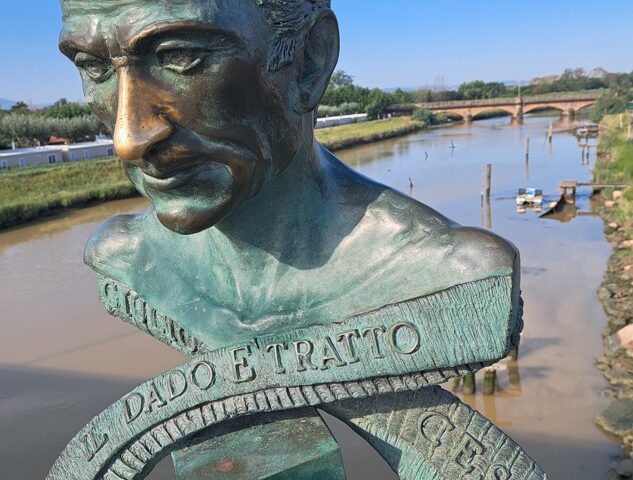

This week, Dorothy Bishop visited Amsterdam to present a fabulous lecture on a topic that has not (yet) received the attention it deserves: “Fallibility in Science: Responsible Ways to Handle Mistakes”. Her slides are available here.

As Dorothy presented her series of punch-in-the-gut, spine-tingling examples, I was reminded of a presentation that my Research Master students had given a few days earlier. The students presented ethical dilemmas in science — hypothetical scenarios that can ensnare researchers, particularly early in their career when they lack the power to make executive decisions. And for every scenario, the students asked the class, ‘What would you do?’ Consider, for example, the following situation:

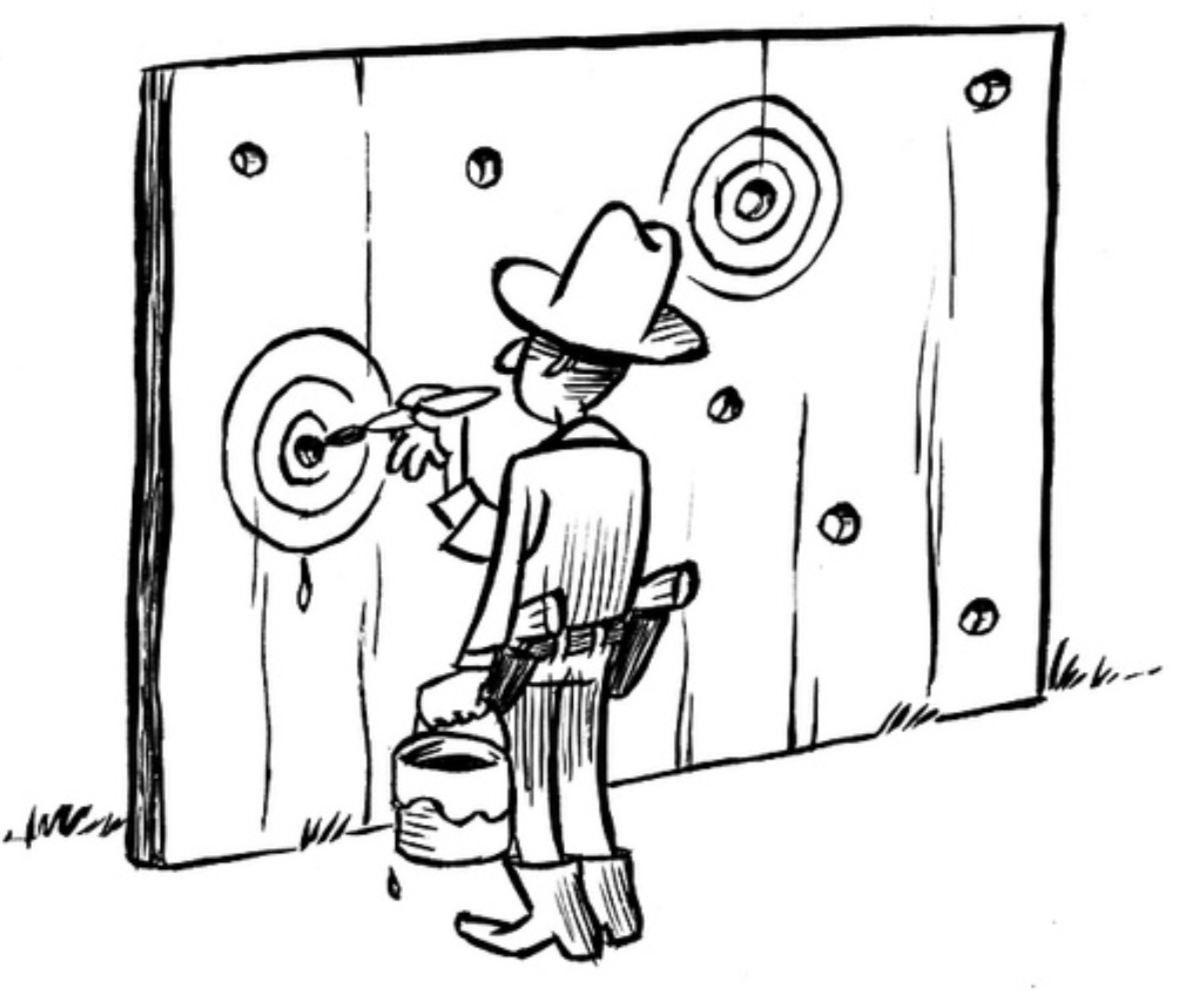

SCENARIO: You are a junior researcher who works in a large team that studies risk-seeking behavior in children with attention-deficit disorder. You have painstakingly collected the data, and a different team member (an experienced statistical modeler) has conducted the analyses. After some back-and-forth, the statistical results come out exactly as the team would have hoped. The team celebrates and prepares to submit a manuscript to Nature Human Behavior. However, you suspect that multiple analyses have been tried, and only the best one is presented in the manuscript.

DILEMMA: Should you rock the boat and insist that those other, perhaps less favorable statistical analyses are presented as well? I maintain that very few researchers would take this course of action. The negative consequences are substantial: you will be seen as disloyal to the team, you will appear to question the ethical compass of the statistical modeler, and you will directly jeopardize the future of the project that you yourself have slaved on for many months. In the current publication climate, presenting alternative and unfavorable statistical analyses –something one might call “honesty”– is not the way to get a manuscript published. The dilemma is exacerbated by the fact that you are a junior researcher on the team.

So, in the above scenario, what would you do?

When I considered this scenario myself, I had to think about the dog trapped in a dishwasher (you can Google that). Basically, the dog is just stuck in an unfortunate situation. I cannot seriously advise early career researchers to rock the boat, as this could easily amount to career-suicide. On the other hand, by not speaking up you accrue bad karma, and deep down inside you know that this is not the kind of science that you want to do for the rest of your life. You have not exactly been “Bullied into Bad Science”, but you’ve certainly been “Shifted into Shady Science”.

Luckily, there is a solution. Not for the poor dog — it is just stuck and you might have to think about getting a new one. But you can take measures to prevent the new dog from getting trapped. And one of the better measures, in my opinion, is to use preregistration.

With preregistration, the statistical analysis of interest has been determined in advance of data collection, hopefully leaving zero wiggle room for hindsight bias and confirmation bias to taint the analysis procedure. Importantly, you can still present exploratory analyses, as long as they are explicitly labeled as such.

But how about getting that manuscript published in Nature Human Behavior? You’ve prevented the dog from getting stuck in the ethical dishwasher, but you still desire academic recognition. Fortunately, you can have your cake and eat it too. Nature Human Behavior is among a quickly growing set of journals that have adopted Chris Chambers’ Registered Report format. In the RR format, you first submit a research plan, including a proposed method of analysis. As soon as the editor and reviewers are happy with the plan, you receive IPA (in-principle acceptance): an iron-clad promise that, as long as you do the intended work, and as long as do it carefully, the resulting manuscript will be accepted for publication independent of the outcome.

A Bayesian Thought

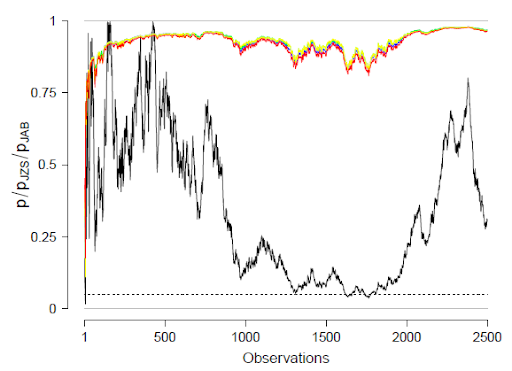

Some people appear to be under the impression that preregistration is useful only for frequentists, but serves no purpose for Bayesians. I believe these people are confused — as you may expect, cheating and self-delusion are bad form in any statistical paradigm. A detailed discussion with concrete examples awaits a future blog post.

Take-Home Message

Preregistration is a good way to prevent the subtle ethical dilemmas that beset empirical researchers on an almost daily basis.

Like this post?

Subscribe to the JASP newsletter to receive regular updates about JASP including the latest Bayesian Spectacles blog posts! You can unsubscribe at any time.

About The Author

Eric-Jan Wagenmakers

Eric-Jan (EJ) Wagenmakers is professor at the Psychological Methods Group at the University of Amsterdam.