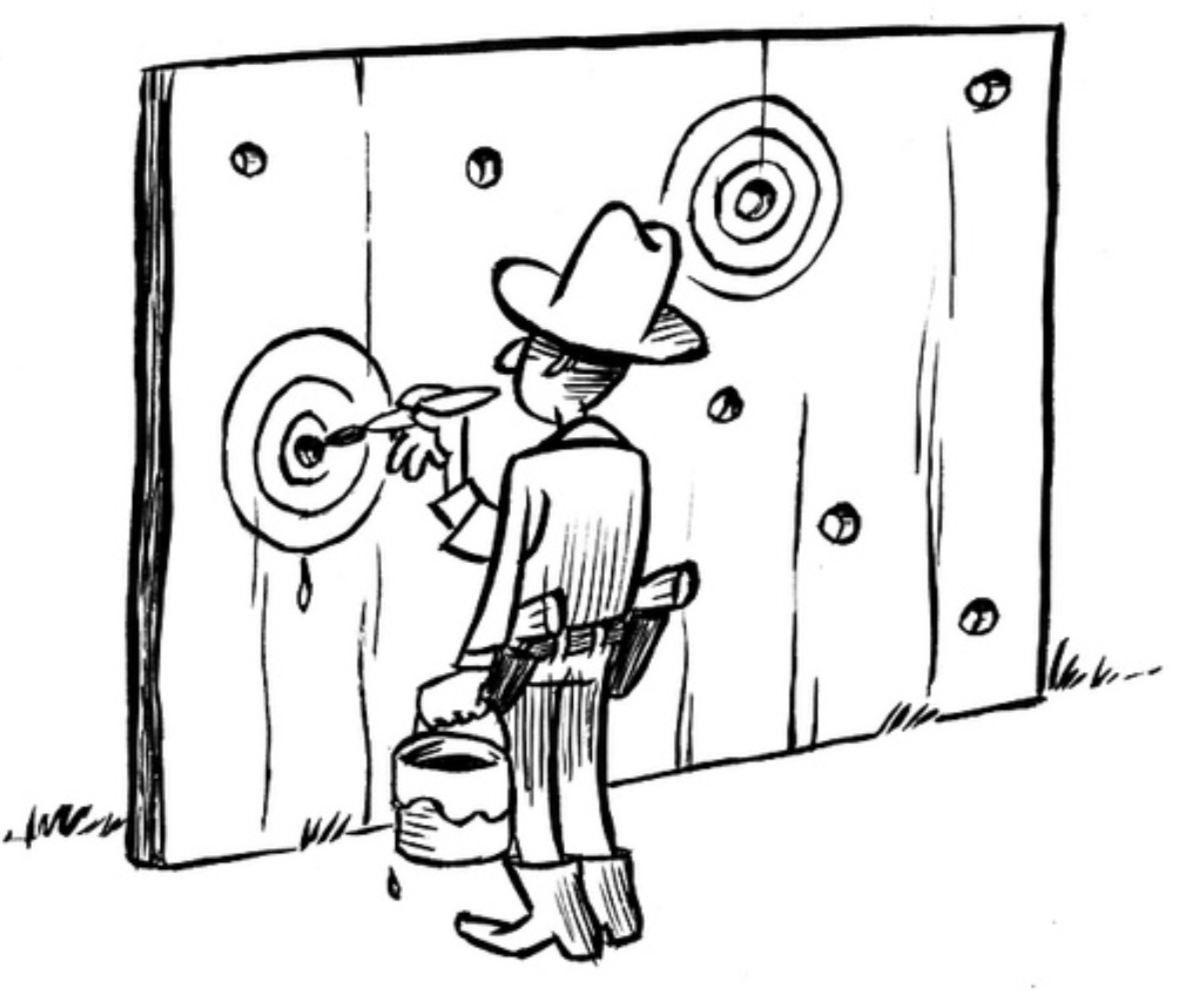

Recently I came across an article by Morton Ann Gernsbacher, entitled “Writing empirical articles: Transparency, reproducibility, clarity, and memorability” (preprint). The author covers a lot of ground and makes a series of good points. Also, as one would hope and expect, the article itself is a joy to read. Here is a fragment from the section “Recommendations for Clarity” — subsection “Write short sentences”:

“Every writing guide, from Strunk and White’s (1959) venerable Elements of Style to the prestigious journal Nature’s (2014) guide, admonishes writers to use shorter, rather than longer, sentences. Shorter sentences are not only easier to understand, but also better at conveying complex information (Flesch, 1948).

The trick to writing short sentences is to restrict each sentence to one and only one idea. Resist the temptation to embed multiple clauses or parentheticals, which challenge comprehension. Instead, break long, rambling sentences into crisp, more concise ones. For example, write the previous three short sentences rather than the following long sentence: The trick to writing short sentences is to restrict each sentence to one and only one idea by breaking long, rambling sentences into crisp, more concise ones while resisting the temptation to embed multiple clauses or parentheticals, which challenge comprehension.”

Gernsbacher is of course entirely correct. In Elements of Style, Strunk and White formulate the same sentiment as follows: “Clarity, clarity, clarity. When you become hopelessly mired in a sentence, it is best to start fresh; do not try to fight your way through against the terrible odds of syntax. Usually what is wrong is that the construction has become too involved at some point; the sentence needs to be broken apart and replaced by two or more shorter sentences.”

Luckily there are exceptions to every rule, and some writers are able to produce long sentences that remain crystal clear from start to finish. True, constructing such sentences requires considerable skill, a lot of self-confidence, and the liberal use of punctuation signs such as the semicolon and the em-dash. When successful, however, such sentences can leave a lasting impression (when unsuccessful, they will also leave a lasting impression

“It is seen in this essay that the theory of probabilities is at bottom only common sense reduced to calculus; it makes us appreciate with exactitude that which exact minds feel by a sort of instinct without being able ofttimes to give a reason for it. It leaves no arbitrariness in the choice of opinions and sides to be taken; and by its use can always be determined the most advantageous choice. Thereby it supplements most happily the ignorance and the weakness of the human mind. If we consider the analytical methods to which this theory has given birth; the truth of the principles which serve as a basis; the fine and delicate logic which their employment in the solution of problems requires; the establishments of public utility which rest upon it; the extension which it has received and which it can still receive by its application to the most important questions of natural philosophy and the moral science; if we consider again that, even in the things which cannot be submitted to calculus, it gives the surest hints which can guide us in our judgments, and that it teaches us to avoid the illusions which offtimes confuse us, then we shall see that there is no science more worthy of our meditations, and that no more useful one could be incorporated in the system of public instruction.” (Laplace, 1902, p. 196)

I won’t rewrite the last sentence as a series of shorter sentences in order to demonstrate that the dramatic effect is entirely lost. One may speculate whether such a sentence, presented as part of an academic article, would manage to make it through the modern review process unscathed; reviewers might rightly or wrongly infer that the author is just a little too confident. One imagines the infamous “Reviewer 2” will offer something along the lines of “The final sentence is too pompous, dramatic, and long. The arguments can be put in a list or a table. Also, I’d like to see more attention paid to the practical difficulties of teaching Bayesian inference in schools”…

References

Gernsbacher, M. A. (in press). Writing empirical articles: Transparency, reproducibility, clarity, and memorability. Advances in Methods and Practices in Psychological Science. DOI: 10.1177/2515245918754485. Preprint.

Laplace, P.-S. (1829/1902). A Philosophical Essay on Probabilities. London: Chapman & Hall.

Strunk Jr., W. & White, E. B. (2000). The Elements of Style (4th ed.). New York: Pearson Longman.

About The Author